What design mindsets did Rand and DeBretteville represent?

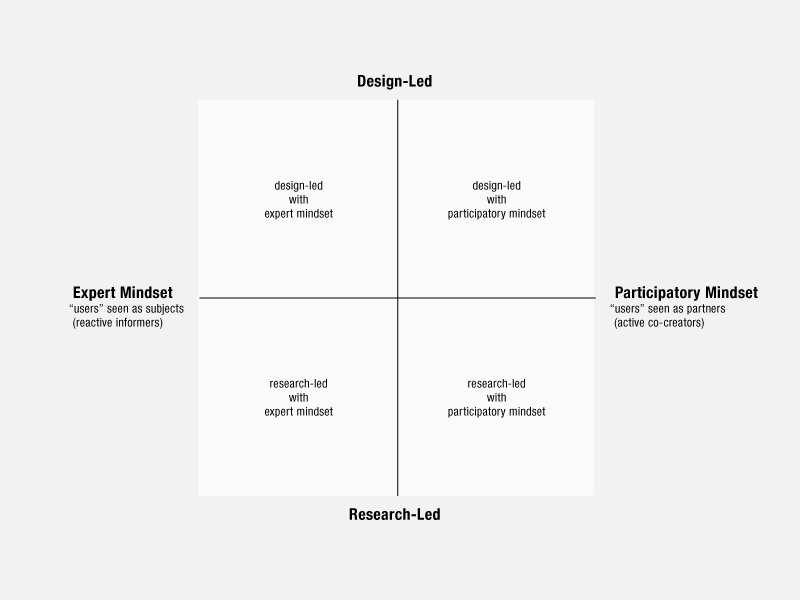

Way back in 2008, Liz Sanders drew a horizontal line. It was part of her Evolving Map of Design Practice and Research. I was interested in the whole map but it was this horizontal line that really grabbed me. It represented a continuum of two opposing mind-sets in the field of design research and practice:

I’ve found myself revisiting this map (and specifically that line) very often. I’ve used, adapted and revisited it at many points in my teaching. Not because it’s a perfect description of the field. More because it enables a conversation about the methodologies we currently associate with graphic design practice and those we don’t. What I love most about this map it that it’s not specifically about graphic design. And that, to me, is what makes it so useful. It helps us zoom out from our sub-disciplinary silos just a little. Not too much, not to the point of abstraction. Just the right amount. I think we get very used to thinking in sub-disciplines. It can be easy to forget that we are part of a larger discipline at all; that other ways of approaching similar questions in the same field can, and do exist.

I also find that absence makes for a powerful talking point. This map really highlights the practices we can evidence and those we cannot and in doing so, makes visible some of the spaces that graphic design is still absent from. Making visible these lesser-knowns, starts to create the conceptual space for the ways of being, thinking and practicing that are yet to emerge.

My students have used this map in different ways

For some it has reaffirmed their position and helped them connect with the broader theories, thinkers and politics of that position.

For others, it has supported them to develop new understandings of the possibilities for their practice by helping them relate it to different methodological perspectives.

For others, it has been an upsetting road block. A disruption to the boundaries they have placed the discipline, and themselves, within.

All diagrams are abstractions. They are less effective at describing ‘reality’ than they are framing ways of seeing. But this one has helped me to speculate on the potential for new ways of working. It has also forced me to consider the gaps between practices. Particularly the ones that ‘exist’ in the world of academic theory and the ones I can actually evidence as operating ‘out there’ in the world. This distinction is depressingly relevant to a generation of students (and an institution) that is so focussed on employability.

A journey along the line…

If we start on the left-hand side of the line we find the expert mindset. In Graphic Design, this is the easiest of the mindsets to identify. Expert designers design for people. The Graphic Design history offers many anecdotes that illustrate this mindset. The most-often trotted out (and by far the most tedious) is the one about Paul Rand and the NeXT logo. When Steve Jobs asked Rand to come up with ‘a few options’ Rand famously said:

“No, I will solve your problem for you and you will pay me. If you want options go talk to other people.”

This was his solution…

The Next Logo designed by Paul Rand Taken from https://garethdavidstudio.com/blog/next-logo-review/

For designers like Rand, design was about process. These processes were carried out by an ‘expert’ in service of a ‘client’ or an ‘audience’. Rand was a firm believer in his process. Alongside his NeXT logo, he produced a sizeable book outlining his entire conceptual process. The moment where Rand explains to NeXT workers how to open a book and in which direction to read it is captured here. If a better (and more damning) caricature of the ‘expert’ graphic design exists, I’d love to see it.

(Oh wait. I have. Most days)

Importantly (for this post at least) Rand was also a design educator. A member of faculty at the Yale University School of Art from the mid 1950s. In 1993, Yale appointed Sheila Levrant de Bretteville as Director of Studies. A feminist scholar, she proposed a move away from the ‘objective’ ‘value-free’ approaches of Modernism, advocating for a ‘person-centred’ approach instead. Rand resigned and convinced Armin Hoffman to do the same.

The Rand-DeBretteville story has always fascinated me. Perhaps because it is a story I can identify with. It seems to reflect the same zero-sum arguments I see playing out in design departments today. Albeit at less dramatic scales and with fewer high profile resignations (regrettably).

Under de Bretteville, the department encouraged students to put and find themselves in their work. It emphasised the students’ desire to communicate, focusing on what needs to be said and to whom they want to say it. You will still find this emphasis on the student in many design departments today. As Ellen Lupton suggested in 1993, it reflected ‘an overall shift in the design profession.’

The (awkward) middle ground

This emphasis on the students intentions bring us up to the position of many a graphic design programme today. Somewhere to the middle of Liz Sanders line. This is an awkward zone to inhabit for both pedagogy and the demands of practice. Mostly because it allows us to step away from the responsibility of the ‘expert’ without fully stepping towards an audience or community. Say we emphasise ‘the students desire to communicate’ over the ‘what and whom.’ How does this change the way we perform, position and critique the discipline? What are the implications for (dare I say this? 😬) quality?

Parallel construction

However, to stop at the first part of de Bretteville’s vision is to miss the bigger picture. She goes on to say;

“The audience is not an audience; it’s a co-participant with you, and it’s also your client. You bring skills, they bring their own knowledge and you are both agencies of knowledge — your knowledge as a designer, their knowledge as a person in need and the community as a group of people in need. It’s a parallel construction rather than a top-down mechanism.”

This notion of ‘parallel construction’ is less discussed and it sits more towards the right side of Liz Sanders map. This is a graphic design culture characterized by a participatory mind-set and it’s approach I see an increasing need to critically explore in graphic design education. Critically because we’re not there yet.

We’re not there yet…

I have often reflected on where my own teaching practices sit on the Rand-DeBretteville scale. Both in terms of the content I teach and the methods I use in teaching. How do content and method emphasise these different mindsets?

Some questions that come up for me (in no particular order):

Process book = Rand’s 100-page expert masterpitch. Discuss.

How do we reward participatory and collaborative approaches in an (education) systems and processes that centre the individual?

Do project presentations and process books necessitate a linear logic? Regardless of whether that was the case or not?

How do we understand and foreground intention in student work?

Are we not biased to certain scales of intention?

Are we dismissive of certain contexts or applications of intention?

How is ideology framed (and how it is challenged)?

‘Slogans in nice typefaces won’t save the human races’

The move to centre ‘socially engaged practices’ in graphic programmes will lack any power if we are still employing expert mindsets and approaches. Somewhere between participatory and expert is a rather patronising and paternalistic framing of graphic design practices as ‘help.’

‘Helping’ people. ‘Helping’ planet. Yuck.

Graphic design as well-meaning, un-informed, nicety. We need a better way of describing what these practices bring to the world.

The question I ask myself as an educator is how we frame this desire, often expressed by students, to ‘help?’ And this is where I (and my students) have found conceptual tools like Liz Sanders map useful. This simple visual device helps us discuss the bigger questions.

disciplinary,

epistemological,

ontological,

philosophical,

phenomenological,

questions.

The things we have avoided for way too long.

How do we understand and describe the different approaches and mindsets that are emerging in the design field?

How do we understand the role of our disciplinary methods in relation to them?

What sense do they give us of the possibilities of practice?

How do we begin to locate the knowledge and skills we need to approach complexity - graphically?

In short, how do we create the methodological literacy amongst graphic design students. The sort that makes their desire to ‘help’…… helpful?

This is an unfinished thought…